POLYGRAPHS IN TEXAS

History of Per Se Rule – Scientific evidence which is shown to be relevant and reliable is admissible under Tex. Rules of Evid. 702);

Perkins v. State, 902 S.W.2d 88, 92-95 (Tex. App. – El Paso 1995, pet. ref’d) (setting forth brief chronological analysis of Texas polygraph evidence law under common law and the Texas Rules of Evidence). It was also based upon the rationale that there were many potential sources of error in the test itself including the examiner’s competency, the jury’s tendency to accord the test too much value, the lack of standardization, as well as the difficulty evaluation of examiners’ opinions posed for a jury. Romero, 493 S.W.2d at 210-11.

Hernandez v. State, 10 S.W.3d 812, 818 (Tex. App. – Beaumont 2000, pet. ref’d)

With the enactment of the rules of evidence, Texas Rule of Evidence 702 became the relevant governing authority. Perkins, 902 S.W.2d at 93. However, Rule 702 has been interpreted to likewise exclude polygraph evidence. See id. The courts have also refused to reconsider the ban in light of Kelly v. State, 824 S.W.2d 568 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992). See, e.g., Landrum v. State, 977 S.W.2d 586 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) (Meyers, J., dissenting, joined by Judge Price, argued that the per se ban on polygraph evidence should be reconsidered in light of Kelly and Hartman v. State, 946 S.W.2d 60 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) which held that scientific evidence which is shown to be relevant and reliable is admissible under Tex. Rules of Evid. 702)

The rule is the same whether the evidence is offered by the State or the defendant. See Castillo v. State,

739 S.W.2d 280, 293 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987). Nor will a stipulation render the results admissible; the

rationale of the rule being that a stipulation will not render the test more reliable. Nethery, 692 S.W.2d at

700; Fernandez v. State, 564 S.W.2d 771, 773 (Tex. Crim. App. [Panel Op.] 1978); Romero, 493 S.W.2d at

212-13. However, the invited error doctrine applies, and so, the door may be opened to polygraph evidence.

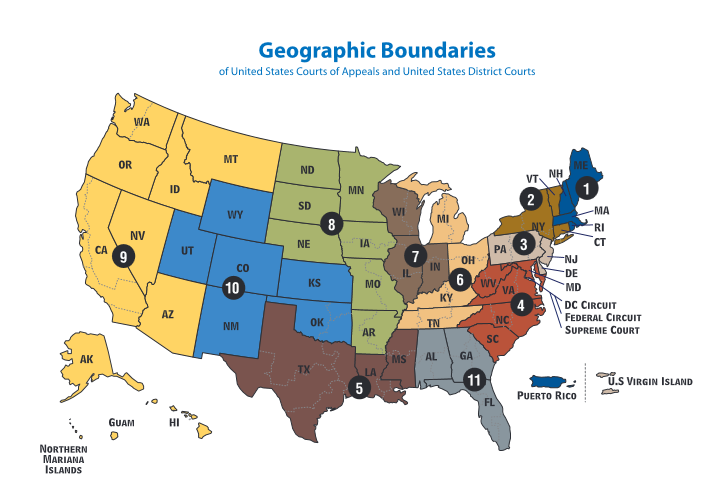

United States Courts Of Appeals

POLYGRAPHS IN THE FEDERAL COURTS – “Circuits that have not yet permitted evidence of polygraph results for any purpose are now the decided minority.” United States v. A & S Council Oil Co., 947 F.2d 1128, 1134 n.4 (4 Cir. 1991).

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. There are 13 U.S. courts of appeals, which are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals from the U.S. district courts within their borders, plus the District of Columbia Circuit, which covers only Washington, D.C., and the Federal Circuit, which hears appeals from federal courts across the United States in cases involving certain specialized areas of law. The courts of appeals also hear appeals from some administrative agency decisions and rule making, with by far the largest share of these cases heard by the D.C. Circuit. Appeals from decisions of the courts of appeals can be taken to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The United States courts of appeals are considered the most powerful and influential courts in the United States after the Supreme Court. Because of their ability to set legal precedent in regions that cover millions of Americans, the United States courts of appeals have strong policy influence on U.S. law. Moreover, because the Supreme Court chooses to review fewer than 3% of the 7,000 to 8,000 cases filed with it annually, the U.S. courts of appeals serve as the final arbiter on most federal cases.

Fifth Circuit

In United States v. Posado, 57 F.3d 428 (5th Cir.1995), the Fifth Circuit overturned its per se rule

against admission of polygraph evidence. The Court decided to “remove the obstacle of the per se rule”

because it was based on outdated concepts about the polygraph’s technical ability and legal precedent which had been overruled by the Court (namely Daubert’s overruling of Frye). In its opinion, the Court also noted that in recent years its view of polygraph evidence had “expanded somewhat”:

See Bennett, 883 F.2d at 405-06 (magistrates may consider polygraph evidence when determining

whether probable cause to issue an arrest warrant exists);

After Daubert, a per se rule is not viable. Because no panel has squarely addressed the issue of polygraph admissibility since Daubert, en banc consideration is not required for this decision. Id. at 433. Concerning technological advances, the Circuit further noted that modern research indicates a seventy to ninety percent accuracy rate. Id. at 434.

The Court prescribed a three-step inquiry: (1) the Court determines whether the evidence is relevant and

reliable pursuant to Daubert; (2), the Court determines whether the evidence will assist the trier of fact in

determining a fact at issue; and (3) the court must decide if the evidence has an unfairly prejudicial effect

that would substantially outweigh its probationer value under Rule 403. Id. at 32-35. In United States v.

Dominguez, 902 F.Supp. 737 (S.D. Tex.1995), the Southern District promulgated several factors to consider

in making this particular balance:

1) That all parties be present to observe the proceedings.

2) That there be a legal commitment irrevocably allowing the admission of the results by both

sides.

3) That the subject commit to be examined by any polygraph expert designated by the other side.

4) When more than one exam is contemplated, the choice of the first examiner take place by

chance.

5) That the pre-test interview be allowed by all sides with all sides present.

6) That the post-test interview be allowed by all sides with all sides present.

7) That immediately prior the test the subject be examined for any sedative or drugs in his body.

8) That the rules that do not admit character evidence for truthfulness be legally waived.

9) That no questions be permitted to the mental state of the defendant at the time of the alleged

commission of the event.

10) The failure of the Defendant to make himself available to testify in the case should also be a

consideration.

Compare United States v. Pettigrew, 77 F.3d 1500, 1514 (5 Cir. 1996) (finding no abuse of discretion in district court’s exclusion of polygraph evidence)

Ulmer v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 897 F. Supp. 299 (W.D. La. 1995) (holding that polygraph tests administered by certified polygraphist at request of investigator for state fire marshal’s office were admissible in jury trial on insureds’ claims)

United States v. Zertuche-Tobias, 953 F. Supp. 803, 807 (S.D. Tex. 1996) (citing problems with both reliability and methodology and noting failure to comply with Dominguez safeguards)

The Northern District has nevertheless recently indicated that the age-old suspicion of polygraph evidence remains. See Tittle v. Raines, 231 F. Supp.2d 537, 552 (N.D. Tex. 2002) (noting that “[t]here is nothing sacrosanct or magical about a polygraph, and its reliability or effectiveness has not gained universal acceptance.”).

Gibbs v. Gibbs, 210 F.3d 491, 500 (5 Cir. 2000) (concluding that polygraph evidence was properly admitted in bench trial)

The History of Polygraph Evidence

The first decision addressing the admissibility of polygraph evidence was Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923). The issue in Frye was the admissibility of the systolic blood pressure test, an unsophisticated precursor to the modern polygraph. The Frye court excluded the test, finding the

evidence was not admissible unless the proponent of the evidence showed that the science involved with this test was generally accepted in the relevant scientific community from which it emerged. The Frye test

subsequently became the primary standard for determining the admissibility of scientific evidence throughout the country.

Following Frye, for 50 years, virtually every state and federal court refused to admit polygraph

evidence. In 1993, the Supreme Court replaced the Frye test with the standards set forth in Daubert v.

Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579, 113 S.Ct. 2786, 125 L.Ed.2d 468 (1993). Under Daubert, the

proper inquiry concerning scientific evidence is based on Federal Rule of Evidence 702 and asks whether

the scientific evidence is relevant and reliable. The pertinent factors to consider under Daubert included,

(1) whether the theory or technique on which the testimony is based is capable of being tested; (2) whether the technique has a known rate of error in its application; (3) whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer review and publication; (4) the level of acceptance in the relevant scientific community of the theory or technique; and (5) the extent to which there are standards to determine the acceptable use of the technique. None of the factors was considered dispositive and the test was to be applied in a flexible manner. See also Kelly v. State, 824 S.W.2d 568 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992) (adopting a similar test under Texas Rules of Evidence).

Following Daubert, state and federal courts throughout the country began to re-examine the per se ban

on polygraph tests. The results have ranged from a significant number of jurisdictions adhering to the per

se rule against admissibility, while others relaxed their rules and began to admit polygraphs in limited

circumstances. In fact, the per se exclusion of polygraph tests is now the minority view among the Federal

Circuits. See United States v. A & S Council Oil Co., 947 F.2d 1128, 1134, n.4 (4th Cir. 1991) (noting that

circuits that have not yet permitted evidence of polygraph results for any purpose are now in the decided

minority). New Mexico has the most liberal rules and generally admits polygraph evidence in the same way as other expert evidence. See State v. Dorsey, 88 N.M. 184, 539 P.2d 204 (N.M. 1975); New Mexico Rule of Evidence 11-707. At least fourteen states follow a standard for admissibility similar to Daubert. See

Peeples, Exculpatory Polygraphs in the Courtroom: How the Truth May Not Set You Free, 28 Cumb. L. Rev.

77, 115, n.6 (1997-98).

In United States v. Scheffer, 523 U.S. 303, 118 S.Ct. 1261, 140 L.Ed.2d 413 (1998), the U. S. Supreme

Court considered the constitutionality of Military Rule of Evidence 707 which bans the use of polygraph

evidence in all court martial proceedings. This rule was promulgated by the President in his capacity as

Commander-in-Chief. The issue in Scheffer was whether the per se ban interfered with the defendant’s

constitutional right to present a defense under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. See, Chambers v.

Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284, 93 S.Ct. 1038, 35 L.Ed.2d 297 (1984) and Rock v. Arkansas, 483 U.S. 44, 107

S.Ct. 2704, 97 L.Ed.2d 37 (1987). A four judge plurality of the Court (Thomas, Rehnquist, Scalia, Souter)

upheld the rule, noting that there was no general consensus within the scientific community about the

reliability of polygraph evidence and that the rule provided a safeguard against the admission of unreliable evidence. The plurality opinion also found that a jury might be unduly influenced into giving excessive weight to polygraph testimony. Additionally, the Court plurality found that collateral litigation concerning the polygraph could distract the jury from the more important issues of the trial. The court found all of these governmental interests to be necessary and legitimate and, therefore, upheld Military Rule 707 against a constitutional challenge under the Fifth and Sixth Amendment right to present a defense.

A four judge concurrence (Kennedy, O’Connor, Ginsburg, Breyer) agreed that enforcing Military Rule

of Evidence 707 was not unconstitutional because there was continuing disagreement among experts and

courts regarding the reliability of polygraphs. However, these four justices argued that a per se rule of

exclusion was not justified. Significantly, the plurality opinion held that, “individual jurisdictions may reach

differing conclusions as to whether polygraph evidence should be admitted.” 523 U.S. at 312. Justice

Kennedy wrote that, “I doubt, though, that the per se exclusion is wise, and some later case might present

a more compelling case for introduction of the testimony than this one does.” Justice Stevens, the lone

dissenter in Scheffer, argued that there should never be a per se rule banning polygraph evidence as such rule violates the constitutional right to present a defense. Justice Stevens also noted that there is much

inconsistency between the government’s extensive use of polygraphs to make security determinations and the government’s argument in Scheffer that the tests are inaccurate.

Scheffer has often been misunderstood as standing in favor of the per se exclusion of polygraph

evidence. In fact, at least 5 out of 9 justices expressed views against a per se exclusion, leaving the issue

very much alive in the lower courts. Quoted from a great resource by Sorrels and Udashen.

Probation Conditions

Ex parte Renfro, 999 S.W.2d 557 (Tex. App. 1999) (Court could properly condition community-supervised probation on periodic polygraph exams.)

Results on Appeal

Long v. State, 10 S.W.3d 389 (Tex. App.-Texarkana 2000) (Although results of polygraph examination are inadmissible, failure of defendant to object to testimony of polygraph results prevents raising the issue on appeal. Had defendant timely raised an objection to the testimony of polygraph examination results, he would have been entitled to a mistrial.)

Changed Statement

Bradley v. State, 48 S.W.3d 437 (Tex. App. 2001) (Court did not err in refusing to allow defendant to cross-examine state’s key witness with evidence that witness changed his statement after failing polygraph but was not polygraphed to determine truthfulness regarding changed statement.)

Admissibility & Sixth Amendment

Perkins v. State, 902 S.W.2d 88 (Tex. App. 1995) (Polygraph evidence inadmissible under Rule 702, as it does more than assist trier of fact but, rather, impermissible decides an issue for the jury. Also, such rule does not violate defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to obtain favorable witnesses.

Probation Miranda

Marcum v. State, 983 S.W.2d 762 (Tex. App. 14th Dist. 1998) (Polygraph examination administered as part of a court-ordered condition of probation is not an in-custody interrogation for purposes of triggering the need to give Miranda warning.

Military Cadet Confession

Graham v. State, 3 S.W.3d 272 (Tex. App. 1999) (Order to Air Force cadet to stay overnight unrestrained at command center in military institution pending next day’s polygraph test does not constitute apprehension or custody, as such restriction was a product of cadet’s military status. As such, post-polygraph confession is not a product of illegal arrest or detention. Further, prosecutor’s improper reference to defendant’s polygraph examination during opening statement did not require mistrial, as court gave limiting instruction. Additional reference to polygraph by prosecution was not made subject of objection and, as such, defendant waived right to raise as an issue on appeal.)

Per Se Rule

Hernandez v. State, 10 S.W.3d 812 (Tex. App. 2000) (Court declined to re- examine per se rule excluding polygraph evidence at trial.)

Confession

Gomes v. State, 9 S.W.3d 373 (Tex. App. 1999) (Police conduct following polygraph examination not sufficient to overcome voluntarism of defendant’s confession.)

Firefighter Pre Employment

Andrade v. City of San Antonio, 143 F.Supp.2d 699 (W.D. Tex. 2001) (Upholding pre-employment polygraph screening for firefighter positions.)

Revocation Hearing

Leonard v. State, 2021 WL 715981 (Tex. Crim. App. 2012) (Reversing lower appellate court, the Court held that polygraph evidence is admissible in a revocation hearing on defendant’s discharge from a sex offender treatment program involving community supervision if it qualified as the basis for an expert opinion under Texas Rules of Evidence 703 and 705(a). Such evidence is permission because revocation hearings are administrative proceedings, in which there is no jury and the judge is not determining the guilt of the original offense.)

Probable Cause

Guardiola v. State, 20 S.W.3d 216 (Tex. App. 2000) (Failed polygraph cannot, by itself, constitute probable cause for arrest.)

Polygraph in Treatment

Mitchell v. State, 420 S.W.3d 448 (Court of Appeals of Texas, Houston 14th Dist, 2014) Polygraphs offer some value at the diagnostic level, thus sex offenders required to submit to this condition of community supervision is reasonable.